Stereoscopy is a technique used to create the perception of depth when viewing stereoscopic images. Our two eyes enable us to experience a three-dimensional world, caused by the small perspective differences between the left and right eyes. These are interpreted by the brain as “depth”. The perception of depth is called stereopsis.

With stereoscopy it is possible to simulate this process. The most popular way to create stereoscopic images is with a camera. With a conventional camera, stereoscopic images are made by taking one photo, slightly shifting the position of the camera and then taking a second photo. The distance between both positions is called the stereo baseline. The result is two nearly identical photos with only a slight difference in perspective caused by the two different camera positions, similar to the different positions of our eyes. These two pictures form a stereo pair. A stereo camera has two lenses, which are mounted at some distance from each other. With a stereo camera, the two photos can be made simultaneously, without having to move the camera position. The main advantage compared with conventional cameras is that stereo cameras prevent motion between the two photo captures.

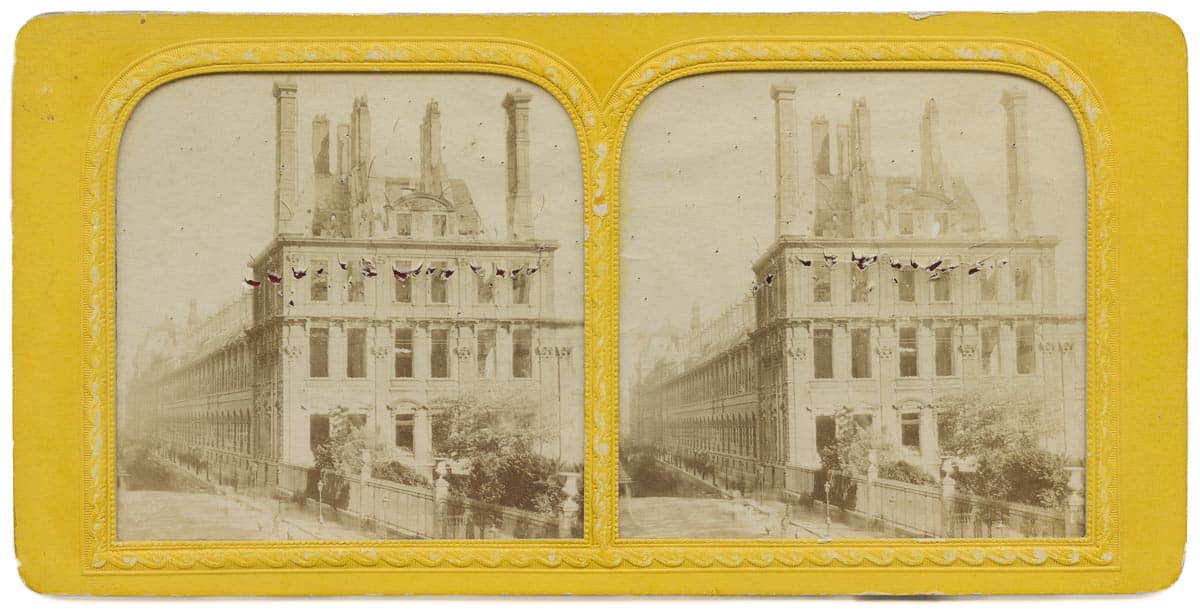

Notice the small perspective differences between the left and right image.

A developed stereo photo is called a stereoview or stereograph. There are several ways to view a stereoview in 3D. The most commonly used method is by using a stereoscopic viewer, better known as a stereoscope. The stereoview is placed in the stereoscope, and both images of the stereoview can be viewed through two lenses: the left image with the left eye and the right image with the right eye. This process allows the viewer to see the image in 3D.

Invention and stereoscopomania

The stereoscope was invented in 1832 and presented for the first time in 1838 by the Englishman Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875). Wheatstone’s invention was a large reflecting stereoscope that could be used for viewing stereoscopic drawings, because photography would not be introduced until a year later with the presentation of the daguerreotype process. The combination of photography and the stereoscope would become decisive for the success of stereoscopy.

The Scotsman David Brewster (1781–1868) introduced an improved and more compact lenticular stereoscope in 1849. His invention was met with little enthusiasm in the United Kingdom, and he found no manufacturer willing to produce his stereoscope. In 1850 he took his prototype to Paris and demonstrated it to the optician Jules Duboscq (1817–1886). Duboscq immediately saw the potential of the device and started producing and selling stereoscopes based on Brewster’s design.

Daguerreotypes were unique and expensive and could not be easily reproduced. They fell into disuse in favour of the new collodion process that was introduced in 1851. Collodion negatives could be used to make multiple copies of the same image on paper and glass. The Great Exhibition was held at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851. During the exhibition, Brewster presented a stereoscope to the British Queen Victoria. She was impressed by the three-dimensional images, and her enthusiasm was a great promotion for stereoscopy. Interestingly, the only source describing this event was Brewster himself and the story may therefore not be true. However, the rise of stereoscopy started and would lead to a real stereoscopic craze called stereoscopomania from 1856 in the United Kingdom and France. Publishers started mass producing and selling stereoviews, and The London Stereoscopic Company boosted its sales with the slogan “no home without a stereoscope”. In the mid-1860s, the craze started to fade and stereo photography slowly died out in the United Kingdom. A revival emerged in the United States and France around 1890.

French glass stereoviews

In the 1851 Great Exhibition, Duboscq was introduced to the magic lantern glass slides of Frederick (1809–1879) and William Langenheim (1807–1874) from the United States. The slides inspired Duboscq to create glass stereoviews, and he had his photographer Claude-Marie Ferrier (1811–1889) travel over from Paris to study the images of the Langenheim brothers.

Duboscq extended the Brewster-type stereoscope by attaching a frosted glass plate to the back of the device to illuminate glass stereoviews. He patented his design in 1852 and paved the way for glass stereoviews, which would become a French specialty. These stereoviews were more expensive but provided a better viewing experience than paper card stereoviews. Ferrier created the first glass stereoviews based on the albumen negative process. They were published by Duboscq, but from 1854 Ferrier continued as an independent photographer. Ferrier partnered with his son, Jacques-Alexandre (1831–1912) and Charles Soulier (c.1840–c.1876) in 1859, and Ferrier père, fils & Soulier became a renowned publisher of high-quality 8.5 x 17 cm glass stereoviews with images of European countries. Ferrier and his successors continued their business until the dawn of the 20th century.

Stereoscopy revival in the 1890’s

The industrialist Jules Richard from Paris who specialised in precision instruments. He introduced the small 45 x 107 mm stereoview glass format and the Vérascope stereo camera in 1893. This new format allowed the design of compact and cheaper cameras and stereoscopes. Richard had momentum because his invention coincided with a growing period in which living standards were improving in France and the invention of the silver gelatin process in 1871 had simplified the making and development of photographs. Other manufacturers in and outside France, like the renowned German manufacturers Ernemann and ICA, adopted the new 45 x 107 mm format. Richard revived stereo photography in Europe. This stereoscopy revival flourished particularly in France and would last well into the 1930s.

Stereo cameras

Before the introduction of the stereo or binocular cameras, the two photos that form a stereo pair were made with conventional single-lens cameras. Josiah Latimer Clark (1822–1898) presented in 1853 a camera that was mounted on a board with grooves that allowed the position of the camera to be changed quickly and consistently between the taking of the two photos. Stereo photos were also made by using a setup of two similar cameras that captured the two images simultaneously. The first stereo camera was patented in 1856 by John Benjamin Dancer (1812–1887).

The main difference with a conventional camera is that a stereo camera has two lenses. When the distance (baseline) between the lenses is 65mm, it is equivalent to the average distance between the two eyes of a human. Earlier stereo cameras could have a larger baseline.

The early photography processes required long exposure times. Exposure was controlled by removing and replacing the lens hoods of the camera’s lenses. When using a stereo camera, it was important that both photos that formed the stereo pair had identical exposure times. In the 1860s, stereo cameras could be equipped with simple shutters. Hinged flaps on the lenses or a swivelling plate were manually operated and could uncover and cover the lenses simultaneously. With the improvements of photographic processes, shorter exposure times became possible in the late 19th century, and more advanced shutters were developed that could precisely control the exposure. To prevent one image overlapping the other, a curtain (septum) was mounted in the camera body between the two lenses.

Stereoviews

Stereoviews that are made by a camera can be characterised by their size and support layer. Many early views had a size of approximately 8.5 x 17 cm, which became an unofficial standard, but many “exotic” stereo formats exist.

Metal

The earliest stereoviews that were made on a fairly large scale were daguerreotypes. A daguerreotype consists of polished silver that is applied to a copper plate. Viewing a stereo daguerreotype can be challenging. The image on the mirror-like silver can cause reflections, which distort the viewing experience and depth effect. Special viewers were introduced in the 1850s to overcome this problem. A daguerreotype is often covered with a glass plate for protection, but this plate can also be decorated with a black passepartout and golden fillets. The two layers are fixed by binding tape. The general size of a stereo daguerreotype is approximately 8.5 x 17 cm, but other sizes exist. Another process that used metal as a support layer was the tintype process. Tintypes were printed on iron plates, but the process was less popular for creating stereoviews.

Glass

Glass stereoviews are also called transparencies or diapositives. The early glass stereoviews measured about 8.5 x 17 cm. These views consist of two or three layers of glass. The extra layer(s) protect the glass plate that contains the photographic emulsion. A frosted glass (verre dépoli) behind the photographic layer hides the background and illuminates the slide equally. The early slides often had the same decorative style as daguerreotypes. Later slides also had a size of 9 x 18 cm.

The large exclusive glass stereoviews were replaced by the smaller 45 x 107 mm and 6 x 13 cm formats in the 1890s. The images of the smaller formats are printed on a single glass layer, without protective cover plate. This makes the photographic emulsion more exposed to scratches and moisture, but they were easier and cheaper to manufacture, especially for the amateur market. Small format glass stereoviews with a protective glass layer are less common. Special types of glass stereoviews are stereo ambrotypes and autochromes.

Paper

The vast majority of stereoviews are printed on paper. Most paper card stereoviews are printed on a thin layer of paper that is mounted on thicker cardboard. The large 8.5 x 17 cm and 9 x 18 cm formats of glass stereoviews remained popular for paper card stereoviews until the 1930s, but smaller 6 x 13 cm cards were also available. A special variant of paper stereoviews are paper transparencies, better known as tissue stereoviews or French tissues. They were introduced in France in 1858. An image is printed on a thin layer of paper, followed by the addition of coloured paint to the back. A thin layer of tissue paper is added to the back to hide the colours and diffuse the light. The two layers are sandwiched between a cardboard frame. With reflective light, a tissue stereoview looks like a normal image. When it is lit from behind, the added colours become visible. Sometimes new details are revealed in the so-called “surprise tissues”. A stereoscope that supports the viewing of both paper card stereoviews and glass stereoviews is needed to fully enjoy a tissue stereoview. Tissue stereoviews exist mainly in the 8.5 x 17 cm format.

Stereoscopes

Stereoscopes can be classified based on different characteristics. A first classification is based on the way in which the depth effect is created. A reflecting stereoscope uses mirrors to view stereoviews in three dimensions. Because of their size, reflecting stereoscopes are impractical compared with the compact refracting and lenticular stereoscopes. The most well-known reflecting stereoscope is the original viewer that was presented by Charles Wheatstone in 1838. The prisms of early refracting or prismatic stereoscopes were replaced by lenses later. Lenses have the ability to magnify an image, which enhances the viewing experience. Most lenticular stereoscopes have the option of focusing the lenses, but cheap or compact viewers may lack this functionality. More advanced stereoscopes might also have the option of inter-ocular adjustment, which adjusts the distance between the lens tubes to support different eye widths.

When looking at the construction and size, there are three types of stereoscopes. The hand-held stereoscope is a compact viewer. Many of these viewers are based on the closed box lenticular stereoscope design that was introduced by Brewster in 1849, and these viewers are referred to as Brewster-type stereoscopes. Tabletop stereoscopes are larger and heavier and must be placed on a table or desk. The third type is the floor standing model. This large viewer was placed on the ground and was suitable for use during exhibitions and other public events.

Closed box stereoscope designs are equipped with a hinged lid that is opened to illuminate paper card stereoviews with reflective light. The inner surface of the lid is provided with silvered-paper and later a mirror to intensify the light. A frosted glass at the rear of the stereoscope is intended to illuminate glass stereoviews with transmissive light. Many viewers have both a hinged lid and frosted glass to support both stereoview types. The interior of the body is painted with matte black to absorb ambient light and prevent reflections.

Another way to classify stereoscopes is by looking at the viewing experience. With a single-view stereoscope, the stereoviews are placed, viewed and replaced one-by-one. By contrast, a multi-view stereoscope allows several stereoviews to be viewed in succession by turning a knob or crank or by moving a lever. The first popular multi-view stereoscopes had stereoviews holders that were attached to a rotating belt or chain. These chain-based or revolving stereoscopes were based on the 1857 patent of Alexander Beckers (1815–1905) from the United States.

The popularity of glass stereoviews in France resulted in the introduction of a new type of multi-view stereoscope that used slide trays, and this type was only suitable for viewing glass stereoviews. The first patented design dates from 1899. It became the design for Jules Richard’s famous Taxiphote stereoscope. Other manufacturers followed Richard and designed similar devices. Most tray-based multi-view stereoscopes share common design principles, but variations in approach and mechanism exist. The general operation of common tray-based stereoscopes is as follows:

Glass slides are placed in a wooden, metal or bakelite tray which is placed into the device. When operating the stereoscope, a glass slide is lifted or pulled out of the tray and placed in front of the lenses. The slide is then placed back, the tray is moved further on a rail and the next slide is loaded. Some designs have a mechanism to quickly jump to a specific slide in the tray. Tray-based devices are the most advanced stereoscopes and offer the best viewing comfort.