45 x 107 mm glass stereoview, La Stéréoscopie Universelle

The First World War was the first war in which photography played a major role. Germany recognised the potential of photography and used photos for propaganda as early as 1914. The images were used to influence public opinion in neutral countries. France realised that it could not stay behind and decided to set up its own photography unit to counter the German propaganda. Following the creation of the film unit La Section Cinématographique de l’Armée (SCA) in February 1915, La Section Photographique de l’Armée (SPA) was founded on 9 May 1915. The unit’s photographers were expected to take images in the following ways:

- From a historical point of view;

- From the point of view of visual propaganda in neutral countries;

- From the point of view of military operations, in order to constitute the documentary archives of the Ministry of War.

10 x 14 cm gelatin silver print

The SPA had to do with three different ministries. The service fell under the direct control of the Ministry of War. The Ministry of Art was responsible for developing and archiving the photos, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs distributed the images for propaganda purposes.

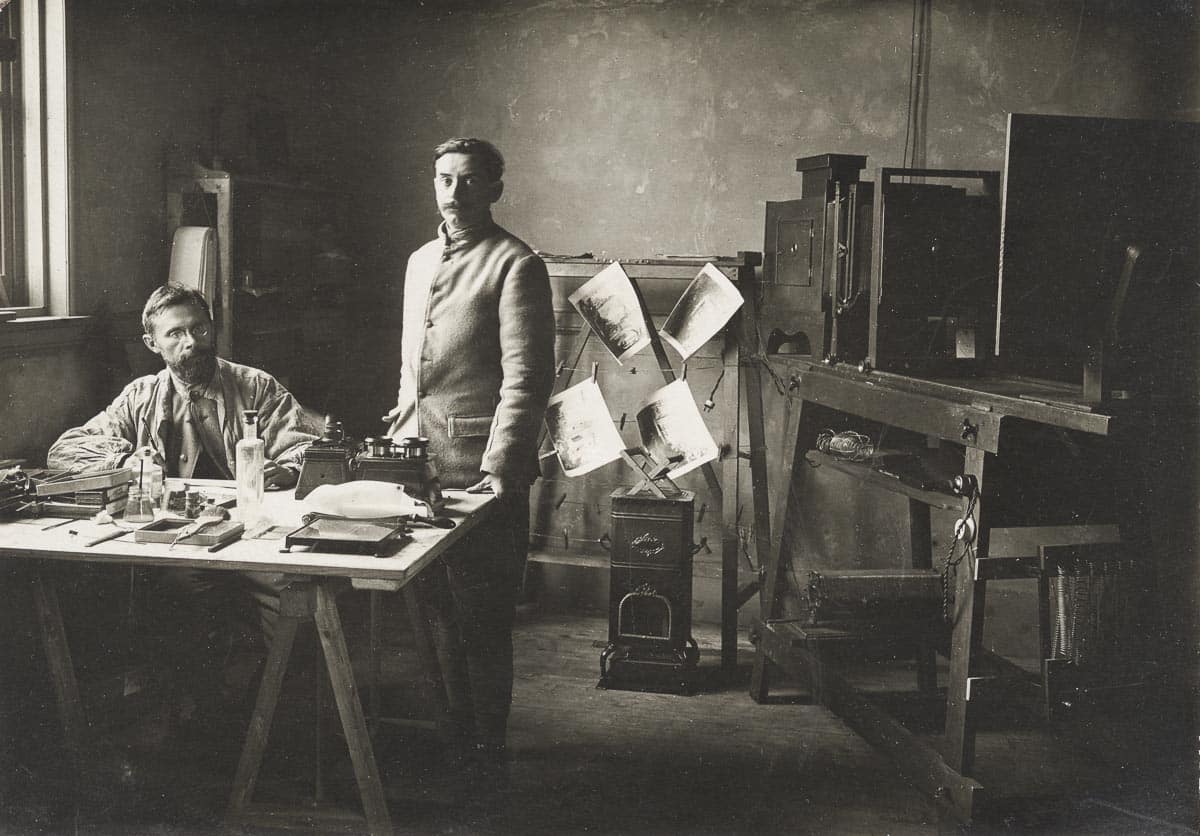

The SPA was led by Lieutenant Pierre-Marcel Lévi, and its headquarters were located on Rue de Valois in Paris. The photographers were called opérateurs, were recruited within the army and could join the SPA if they were unfit for combat duties. At the end of 1917, the unit employed 27 photographers. The service also consisted of a laboratory for developing photos, an archive, an information service and an administration. The SPA merged with the SCA in 1917 to form the Section Photographique et Cinématographique de l’Armée (SPCA). The unit was disbanded after the war.

6 x 13 cm glass stereoview, La Stéréoscopie Universelle

A photography mission to the battlefields was tightly coordinated. The photographer was sent on the initiative of the Ministry of War. Local army commanders were informed of the photographer’s arrival, and the army arranged for the transport. On location, the photographer was accompanied by an officer, who gave detailed instructions on what to shoot. The photographer was expected to keep notes of the photographed scenes and dates so that this information could be archived with the photos. The SPA was, in fact, a propaganda machine. By controlling photography and the distribution of images, the French government was able to regulate how the war was portrayed. The bodies of fallen German soldiers were published, but pictures of French corpses did not reach the public.

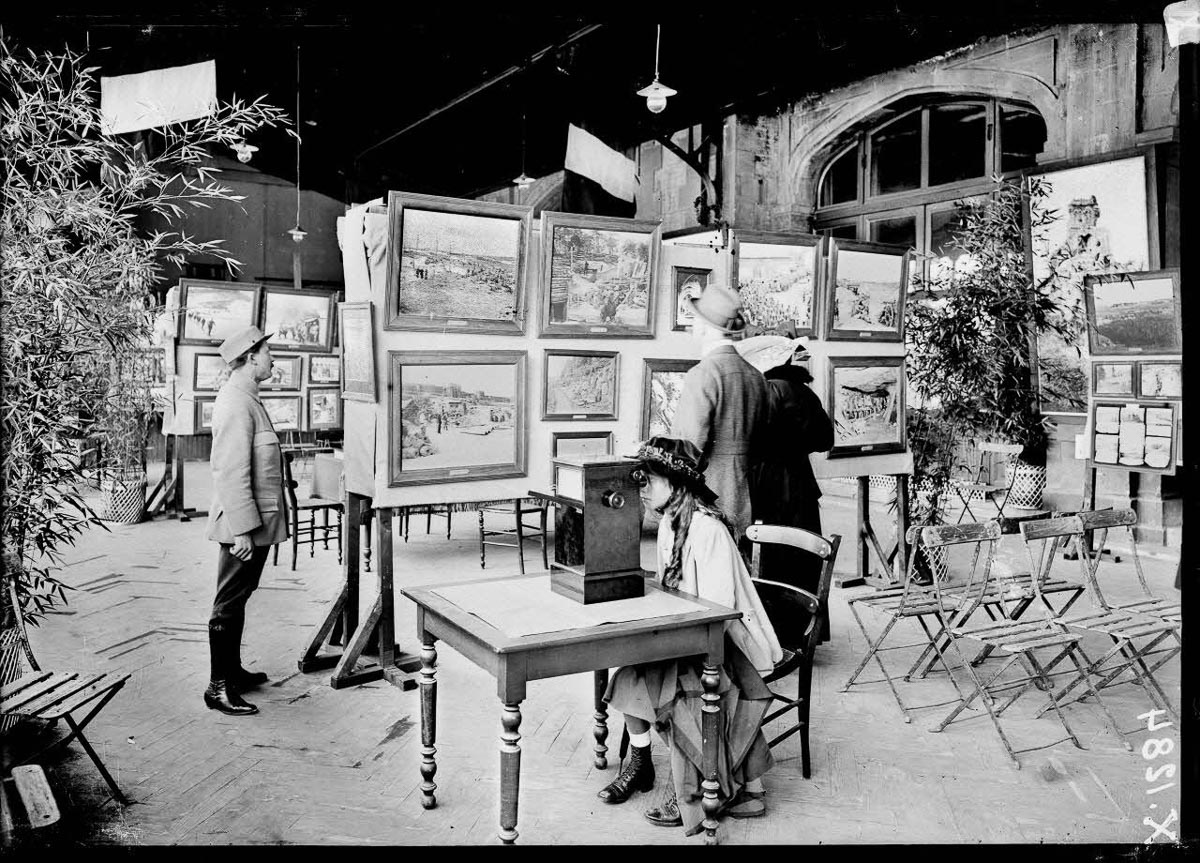

The censored photos were sold during the war to publishers, who released photo albums depicting the course of the war. The albums were affordable so that they could reach a wide audience. The SPA made about 97,000 photos during the war, including about 20,000 stereo photos. The stereo glass plate negatives in the archives are in the 6 x 13 cm format. This format was also used to shoot panoramic photos. A number of cameras could take both stereo photos and panorama photos, such as the Mackenstein Francia No. 4, the Stéréo-Panoramique Leroy and the Gaumont Stéréo-Spido Panoramique. These relatively compact cameras made it possible to shoot closer to the front line, and with light-sensitive negatives, it was possible to shoot without a tripod. The stereoviews of the SPA were intended to be displayed during exhibits where stereoscopes were present.

SPA 31 X 1284, 13 x 18 cm glass plate negative.

© Jacques Agié/ECPAD/Défense (public domain)